It’s always night when I arrive.

The little Embraer 145 lands and shudders to a heavily braked stop at the end of the runway. Then turns and taxis back toward the terminal. Where an air-stair is wheeled up to the side of the plane and we, the passengers, descend.

The air is warm and damp, and smells of wood smoke, jet fuel, silt, and drains.

At the bottom of the stairs I pick up the carry on luggage that never fits in the overhead bins. Then pull my clicking, wheeled bags across the tarmac and onto the concrete sidewalk under a canopy beside a patch of coarse, unnaturally green grass.

The Arrival Hall is a fluorescent lit, eight-foot wide corridor full of gringos attempting to puzzle out the immigration form with its dense, cryptic, oh so foreign instructions.

I am anointed as “one who knows” not for my awful Spanish, but because of my ability to properly fill out this form — information repeated twice. Once in ample spaces at the top of the form. And then again at the bottom in tiny spaces barely big enough for your initials let alone your Appelidos and Nombres. The Immigration Officer will hand this lower portion back to you with the admonition that you must not lose it. That it must be returned on your leaving the country or you will be fined.

Then I gather up my checked bags and pass along another corridor to Aduana. Submit all of my luggage and my “personal item”, as well as the heavy coat I am carrying to the x‑ray machine. Gather these things back up, awkwardly, and smile at the Customs Officer who gestures to the button. Press the button and hope for a green walking-man to light up. I am free to leave.

There are no taxis at the Oaxaca airport. The only way off the grounds is in a private car or one of the cambios, collective mini-buses that load up with ten customers and make a zigzag across the downtown area dropping passengers by ones and twos at various hotels, guest houses, and B&Bs. If you’re feeling flush you can book a “directo.” Basically taking up the entire cambio yourself, at nearly five times the cost of the single ticket. So maybe not.

The trip out of the airport into the city is long, slow, bumpy, and disorienting. I am once again sitting. A last, passive hour added to the 18 that I’ve been traveling. Too much and yet, and yet. There is the sense of having arrived at the carnival, in the house of mirrors, in Wonderland.

The route is familiar but nothing is where I left it. Or maybe everything is where I left it, but disconnected from my memory of the geography. It’s late and the effort to reconnect all of the things I glimpse and barely hear is too much. Flashes of color and language jab thorough the dark. A yellow and black Bardahl’s sign on a tin shack auto repair shop. A rental shop with “todo para sus fiestas” in bright, pink script.

Sounds that will soon be familiar are odd, jarring, and unsourceable. Loud music plays from speakers outside of every kind of shop: cell phone kiosks, clothing stores, the deposito. The elote steam whistle shrills and I startle. The barking of dogs comes from roofs. Chains that hang off of the back of a gas truck jingle manically.

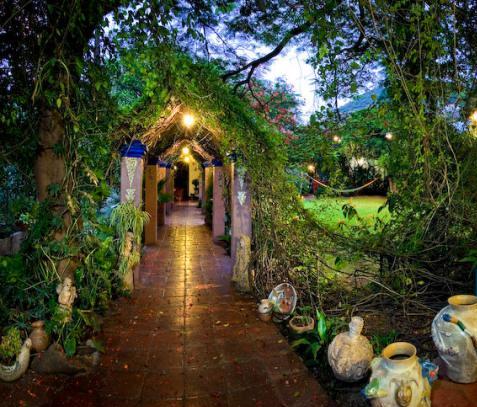

The Casa is always the last stop. Lying as it does at the edge of downtown that is the furthest from the airport. I get out of the cambio and the driver unloads my bags onto the sidewalk in front of a lavender door set into a turquoise wall. I ring the bell. Sometimes the driver gets into the minibus and drives away before the door is opened. Sometimes he waits.

Eventually there’s a click and a scrape as the door is unlocked and opened. A young woman who speaks no English lets me in and roughly takes away my luggage. Insisting on carrying the bags as big as herself along the corridor to my room.

I find some night-clothes; brush my teeth using water from a bottle. Plug in my phone charger.

I fall into a bed at once familiar and strange, and dream of nothing.

Until the bell rings for breakfast.